Opera Director & Designer

Orfeo ed Euridice

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714 –1787)

Gilbert Blin staged Orfeo ed Euridice in 1992 in Drottningholms Slottsteater. This first modern production of the 1769 “Parma Version,” was filmed, recorded, and revived in 1998 as part of the Gluck Festival presented for Stockholm’s year as the EU’s “European City of Culture”.

Drottningholm Slottsteater exploration

Thanks to an invitation from Arnold Östman, Gillbert Blin worked extensively at Drottningholms Slottsteater. Initially, Blin served as a language coach, then progressed to be an assistant director, and ultimately assumed the role of stage director for Orfeo ed Euridice in 1992. At that time, the historic theater was abuzz with activities and discussions centered around the concept of Historically Informed Performance for late-eighteenth-century repertoire.

Artistic leadership

As the Artistic Director in 1988, Arnold Östman articulated the purpose of artistic exploration at the Drottningholms Slottsteater when Gilbert Blin joined as an intern. Östman remarked, “The reason behind our artistic inquiry in the realm of music lies in our endeavor to turn back the clock and rediscover the traditional modes of performance. This same ambition extends to production techniques and acting styles. It should not be interpreted as a lack of creativity or a desire to regress. Rather, it is an imperative in an era where the pursuit of knowledge is intrinsically linked with future-oriented research. It’s only in our time that we have realized how enriching this endeavor can be.”

Drottningholm Slottsteater

1992

Revival 1998

Artists

Arnold Östman, Musical Director

Gilbert Blin, Stage Director

Börje Edh, Costume Design

Marianne Thallaug Wedset, Light Design

Satu Marha Harjanne, Assistant Stage Director

Henrik Löwenmark, Musical Rehearsal

The Gods, the Artist and the Mortal

Article (adapted) for the 1998 program book of the Drottningholm Slottsteater.

The first musicians were the gods

Hermes created the lyre, which he bestowed upon Apollo. The god of the arts produced such harmonious sounds from it on Olympus that the gods forgot their quarrels. Hermes crafted for himself the shepherd’s pipe, and Pan invented the reed flute with its bewitching music. The Muses had no instruments of their own, but their voices were incomparable.

Outstanding Mortals

Thus emerged several mortals whose artistry was so exceptional that they could measure themselves against those divine practitioners. Among them was Orpheus, the most renowned. Being the son of a Muse, the gift of music he inherited from his mother made him unmatched.

Orpheus according to Apollonius

Ovid and Virgil

Two Roman poets, Ovid and Virgil, completed the Orpheus story and provided matching accounts of his unhappy union with Eurydice. Each of their texts vividly describes Orpheus’ strength and increasing power. The musician no longer enchanted only people but also the animals of the field. The power of his singing was so immense that wild beasts followed him; even the rocks, plants, and trees moved. None could resist him; everything, both living and dead, followed him, and rivers changed their courses. Accordingly, Orpheus, the artist, possessed great power: the power to transform the order of the gods, the power to create a new order of nature.

The Orpheus Myth

We know that the gods clung tightly to their privileges (recall the stories of Prometheus and Ixion). The rulers of the realms were disturbed that a mortal could possess such power, and they sought to test Orpheus.

In the Orpheus myth, the twofold experience linked with Eurydice unfolds. The death of his young wife, the first ordeal the singer endured, did not diminish Orpheus’ artistic power; rather, the experience of pain heightened his inspiration. The pain did not silence the poet’s lyre; instead, it made it sing.

The other, more subversive, trial by fire begins when Orpheus is tested with the opportunity to bewitch the very gods. His success with the gods of the Underworld appears to confirm and magnify his power, even causing these gods to yield to it. Has Orpheus become equal to Apollo? Is the artist truly a god?

However, it is through the explicit condition for reunion with Eurydice that his true ordeal arises: he must not turn around. This prohibition triggers one of the fundamental aspects of the human condition: the phenomenon of doubt.

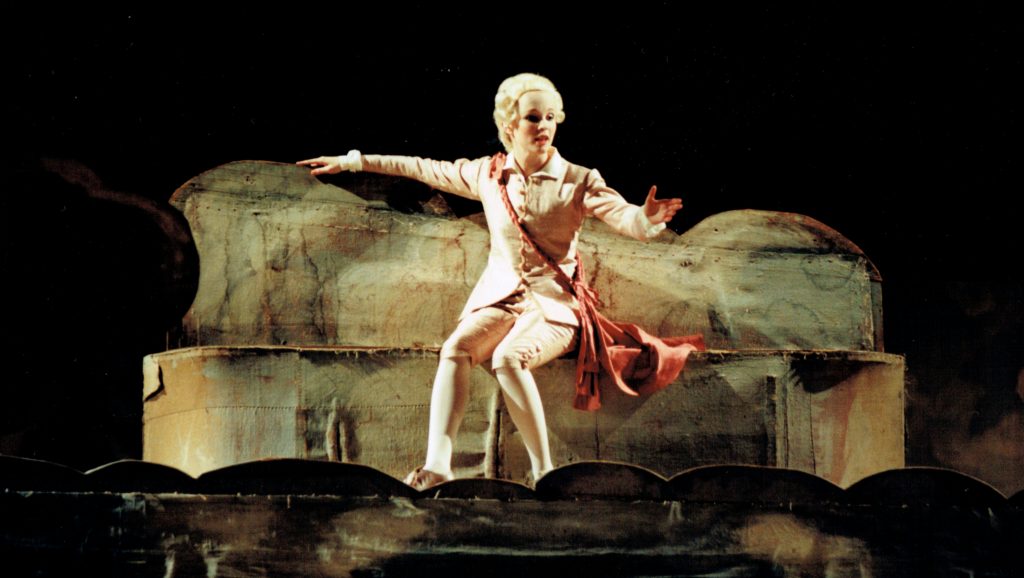

Ann-Christin Biel, Orfeo. Maya Boog, Euridice. Drottningholms Slottsteater, photo Gilbert Blin

Ann-Christin Biel, Orfeo. Maya Boog, Euridice. Drottningholms Slottsteater, photo Gilbert Blin

This doubt emerges during Orpheus’ and Eurydice’s journey from darkness to light, affecting the artist to the point of overwhelming him and revealing his inherent humanity. Orpheus doubts, turns around, and loses Eurydice. The gods can find contentment in this; no matter how great the artist’s power may be, he is not a god. The artist is a human being like everyone else.

Despite losing Eurydice in the end, Orpheus continues to sing, and his power over the world does not diminish; instead, it grows even stronger. Consequently, the gods decide to bring an end to him, for only his death can satisfy them. During their Bacchanalian orgies, the women of Thrace throw themselves upon Orpheus and tear him apart.

However, his head, separated from his body, continues to utter Eurydice’s name, symbolizing the ceaseless love and indomitable hope in the heart of mankind.

1939 - 2023

Arnold Östman

In Memoriam

Get in touch

contact@gilbertblin.eu

Copyright

© 2024 Gilbert Blin, All rights reserved